Mechanisms of Action

Psilocin’s effects on the serotonin receptors, known as 5HT receptors, is known to cause alterations to consciousness, perception, and introspection (Langlitz, 2013; Sessa, 2012).

When psilocybin is metabolized into psilocin, this metabolite brings about psychedelic effects as a result of its effect on the serotonin receptors which are known as 5HT2A receptors. Psilocin is a 5HT2A agonist which means that psilocin binds to the 5HT2A receptors in the same way as serotonin and mimics some of its effects. There are additional serotonin receptors in the brain in addition to the 5HT2A receptor, however psilocin’s role on these other receptors is not well understood (Nichols, 2004).

Hormones

Psilocybin has an impact on the hormones in the body as well as the neurotransmitter serotonin. Psilocybin increases levels of prolactin which lower the levels of your body’s dominant sex hormone–either estrogen or testosterone. At higher doses, psilocybin also increases levels of corticotropin which plays a role in the stress, addiction and depression responses, cortisol which is a stress hormone that also plays a role in repairing tissue, and thyrotropin which impacts neuromuscular function, heart rate, and metabolism. Levels of hormones return to normal values within 5 hours (Gouzoulis-Mayfrank et al., 1999; Hasler et al., 2004).

The Default Mode Network

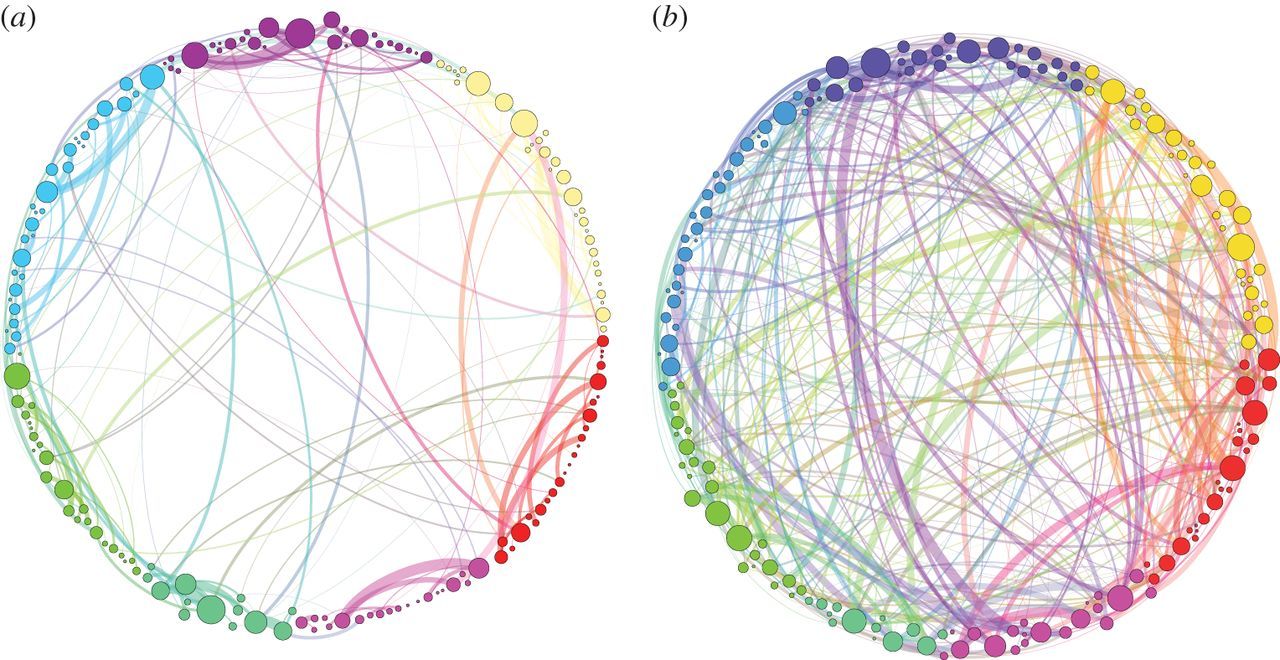

Psilocybin can cause a loosening of organization in brain activity, including strongly conditioned “higher order” cortical patterns, thus decreasing coupling activity in certain functional networks, notably within the default-mode network explained in the video below, while also increasing the repertoire of functional connectivity between other neural networks within and across brain hemispheres (Carhart- Harris et al., 2014; Carhart-Harris, Leech, et al., 2012; Roseman et al., 2014; Tagliazucchi et al., 2014). This improved connectivity can be demonstrated in the figures below comparing a simplified illustration of the brain’s connectivity under the effects of a placebo (left) and under the effects of psilocybin (right).

Adapted from Petri et al., 2014 licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Psilocybin creates new pathways in the brain resulting in improved global neurological connectivity particularly in the brain’s default mode (Rush et al., 2022). It is for this reason why psilocybin is believed to “rewire” the brain with respect to mental health conditions and improved mood.

Brain Activity

Neuroimaging research has shown that psilocybin enhances autobiographical recollection, especially in terms of late phase sensory activations in the occipital pole, left visual association regions, superior parietal lobule, somatosensory cortex, and bilateral auditory cortex; such data supports applications for therapy (Carhart-Harris, Leech, et al., 2012).

Additionally, research has displayed a decrease in amygdala reactivity during emotional processes after psilocybin experiences, which is associated with a more positive mood state; this displays the potential of psilocybin for treating depressogenic symptoms (Kraehenmann et al., 2015). For example, certain research with healthy volunteers displayed that 64% of participants associated their psilocybin experience with an increased sense of wellbeing and satisfaction with their life at a 14-month follow-up, while 61% associated the experience with moderate to extreme positive changes in their behaviour (Griffiths et al., 2008; Griffiths et al., 2006).

Note

While the effects of magic mushrooms are generally associated with psilocybin, there are other psychoactive components that need further investigation. These include baeocystin, norbaeocystin, aerguinascin, norpsilocin and phenylethylamines (Kuypers et al., 2019; Wieczorek et al., 2015). Furthermore, other investigations have found beta-Carbolines in Psilocybe mushrooms which creates an ayahuasca-type synergy of psychoactive compounds and potent monoamine oxidase inhibitors, which have mood-boosting effects and illicit the psychedelic serotonergic effects (Blei et al., 2020).

References

Blei, F., Baldeweg, F., Fricke, J., & Hoffmeister, D. (2018). Biocatalytic Production of Psilocybin and Derivatives in Tryptophan Synthase-Enhanced Reactions. Chemistry. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201801047

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Leech, R., Hellyer, P. J., Shanahan, M., Feilding, A., Tagliazucchi, E., . . . Nutt, D. (2014). The entropic brain: a theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs. Front Hum Neurosci, 8, 20. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00020

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Leech, R., Williams, T. M., Erritzoe, D., Abbasi, N., Bargiotas, T., . . . Nutt, D. J. (2012). Implications for psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy: functional magnetic resonance imaging study with psilocybin. Br J Psychiatry, 200(3), 238-244. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.103309

Gouzoulis-Mayfrank, E., Thelen, B., Habermeyer, E., Kunert, H. J., Kovar, K. A., Lindenblatt, H., . . . Sass, H. (1999). Psychopathological, neuroendocrine and autonomic effects of 3,4- methylenedioxyethylamphetamine (MDE), psilocybin and d-methamphetamine in healthy volunteers. Results of an experimental double-blind placebo-controlled study. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 142(1), 41-50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002130050860

Griffiths, R., Richards, W., Johnson, M., McCann, U., & Jesse, R. (2008). Mystical-type experiences occasioned by psilocybin mediate the attribution of personal meaning and spiritual significance 14 months later. J Psychopharmacol, 22(6), 621-632. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881108094300

Griffiths, R. R., Richards, W. A., McCann, U., & Jesse, R. (2006). Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology, 187(3), 268-283.

Hasler, F., Grimberg, U., Benz, M. A., Huber, T., & Vollenweider, F. X. (2004). Acute psychological and physiological effects of psilocybin in healthy humans: a double-blind, placebo-controlled dose- effect study. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 172(2), 145-156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-003- 1640-6

Kraehenmann, R., Preller, K. H., Scheidegger, M., Pokorny, T., Bosch, O. G., Seifritz, E., & Vollenweider, F. X. (2015). Psilocybin-Induced Decrease in Amygdala Reactivity Correlates with Enhanced Positive Mood in Healthy V olunteers. Biol Psychiatry, 78(8), 572-581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.04.010

Kuypers, K. P. C, Ng, L., Erritzoe, D., Knudsen, G. M., Nichols, C. D., Nichols, D. E., Pani, L., Soula, A., and Nutt, D. (2019). Microdosing psychedelics: More questions than answers? An overview and suggestions for future research. Journal of psychopharmacology, 33(9), 1039-1057.

Langlitz, N. (2013). Neuropsychedelia: The Revival of Hallucinogen Research since the Decade of the Brain. University of California Press.

Nichols, D. E. (2004). Hallucinogens. Pharmacol Ther, 101(2), 131-181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.11.002

Petri, G., Expert, P., Turkheimer, F., Carhart-Harris, R., Nutt, D., Hellyer, P. J., Vaccarino, F. (2014). Homological scaffolds of brain functional networks. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 11(101). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2014.0873

Roseman, L., Leech, R., Feilding, A., Nutt, D. J., & Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2014). The effects of psilocybin and MDMA on between-network resting state functional connectivity in healthy volunteers. Front Hum Neurosci, 8, 204. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00204

Rush, B., Marcus, O., Shore, R., Cunningham, L., Thomson, N., and Rideout, K. (2022). Psychedelic Medicine: A Rapid Review of Therapeutic Applications and Implications for Future Research. Homewood Research Institute. https://hriresearch.com/research/exploratory- research/research-reports/

Sessa, B. (2012). The Psychedelic Renaissance: Reassessing the Role of Psychedelic Drugs in the 21st Century Psychiatry and Society. Muswell Hill Press.

Tagliazucchi, E., Carhart-Harris, R., Leech, R., Nutt, D., & Chialvo, D. R. (2014). Enhanced repertoire of brain dynamical states during the psychedelic experience. Hum Brain Mapp, 35(11), 5442-5456. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22562

Wieczorek, P. P., Witkowska, D., Jasicka-Misiak, I., Poliwoda, A., Oterman, M., & Zielińska, K. (2015). Bioactive alkaloids of hallucinogenic mushrooms. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry, 46, 153-181. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63462-7.00005-1