Working with Parts: Structural Dissociation

Building upon the concept of multiplicity introduced through Internal Family Systems (IFS) in Module 3, we bring a trauma-focused lens to multiplicity with the concept of structural dissociation, a theoretical model of the impact of trauma on the personality first described by van der Hart, Nijenhuis, and Steele (2004).

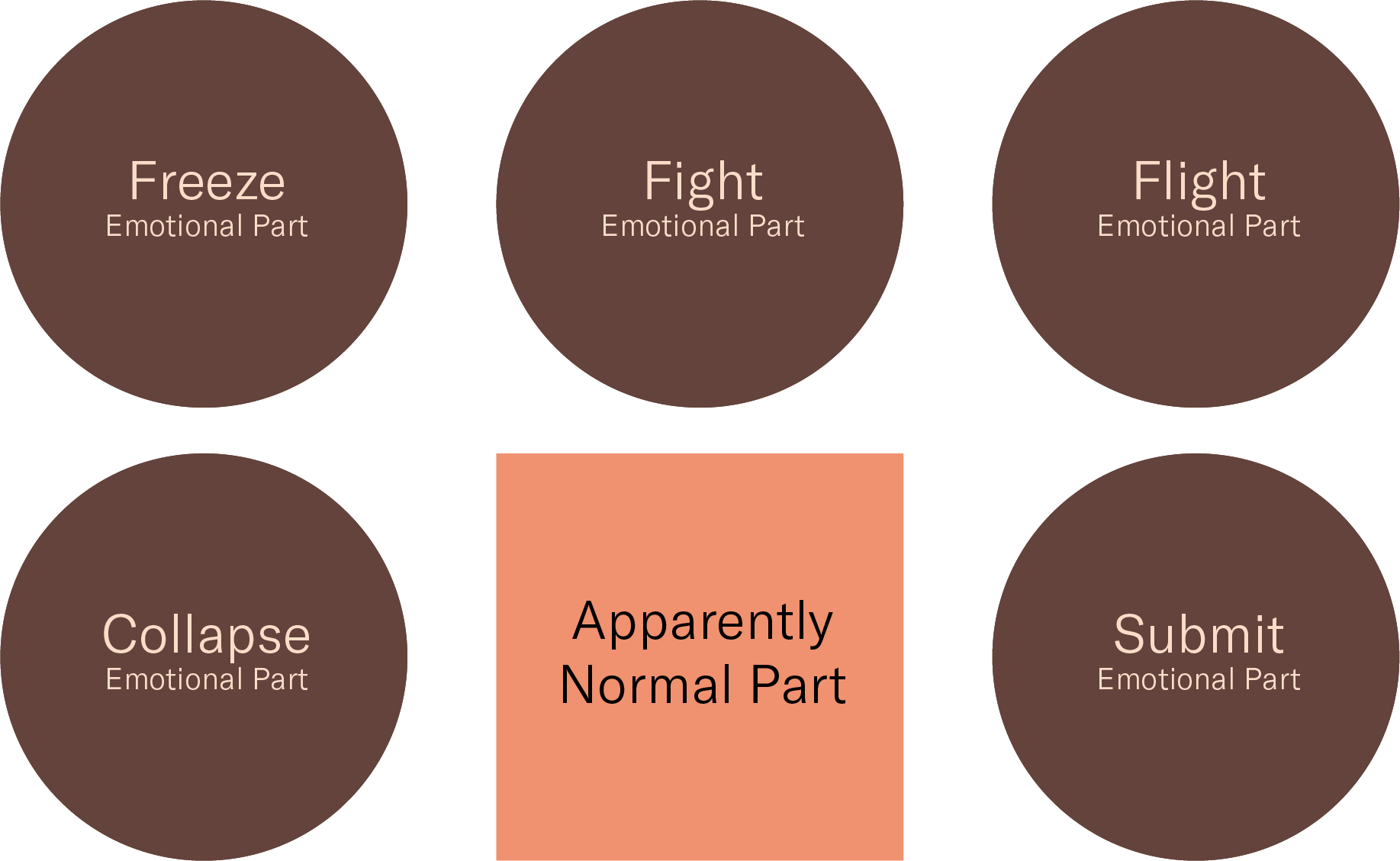

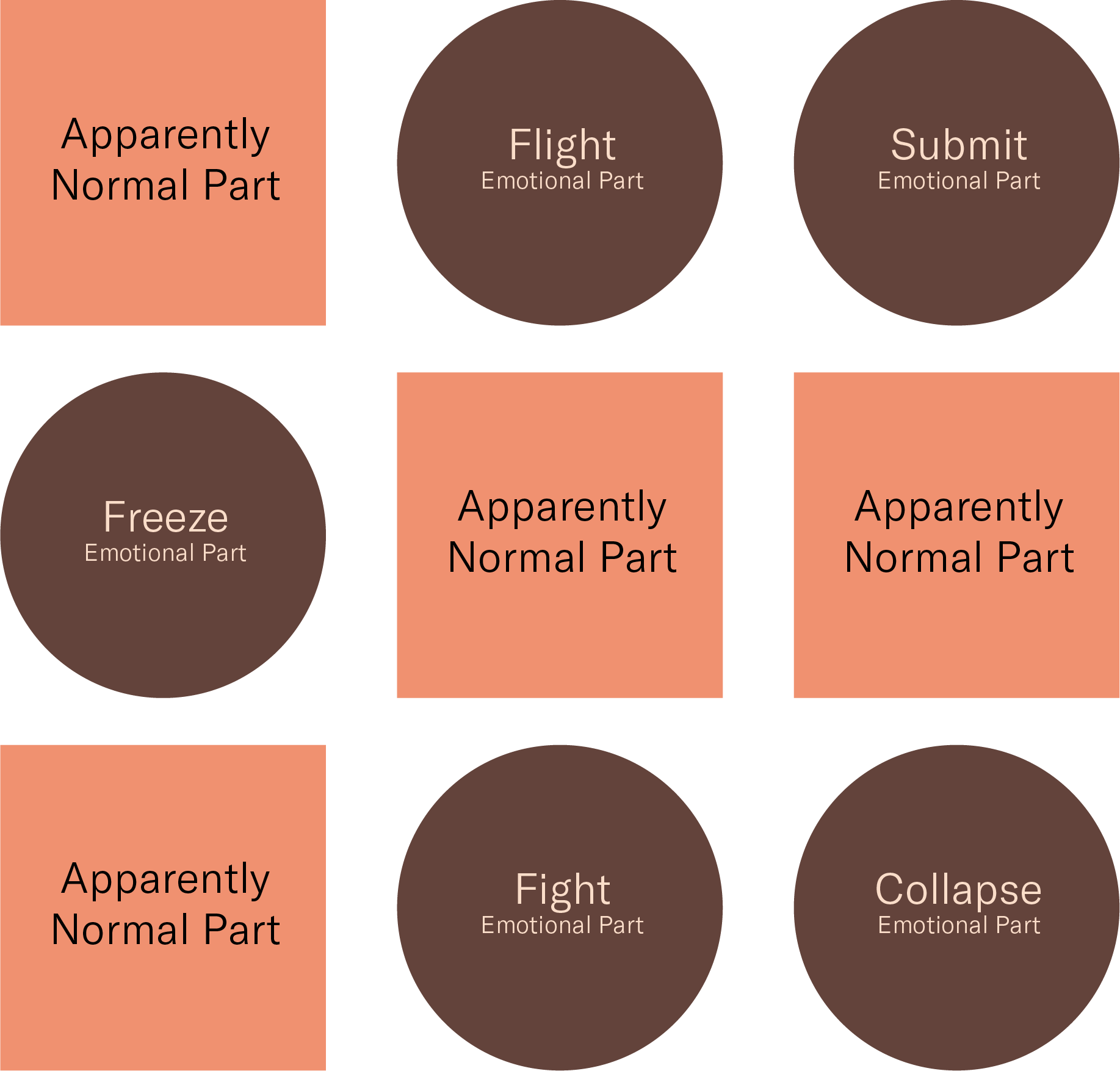

In the context of childhood trauma, there may be many parts that develop each with unique trauma survival strategies, narratives, and attachment drives.

Trauma-Related Structural Dissociation of the Personality

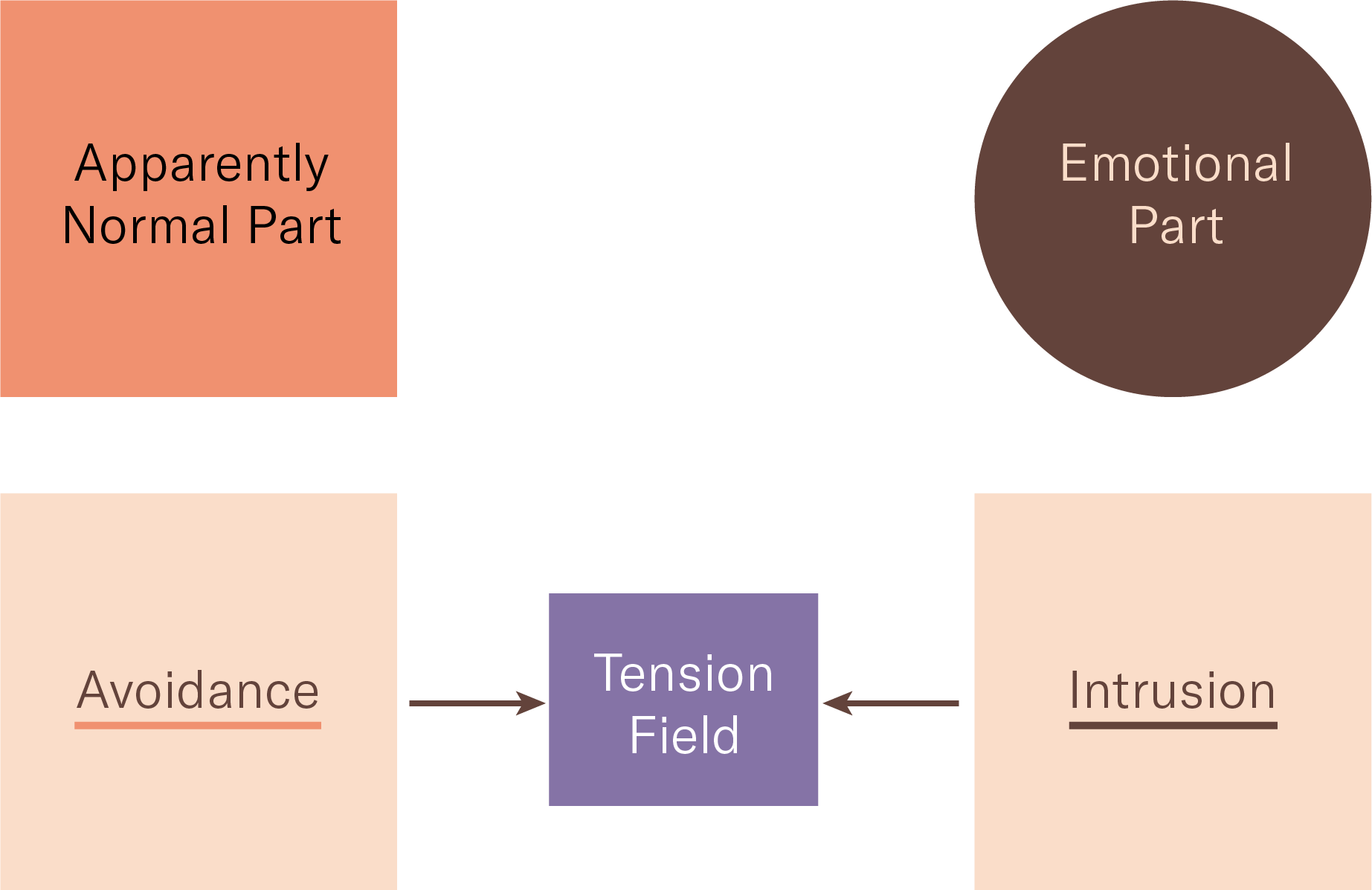

Structural dissociation theory describes a fragmented self-system in which an “apparently normal part” responsible for activities of daily living coexists with parts of self that hold and are preoccupied with traumatic experience (Van der Hart, 2006; Fisher, 2017). Structural dissociation becomes more pronounced in the face of complex trauma. The presence of multi-layered trauma often creates a more complex, secondary, or tertiary clinical picture in which the client’s activities of daily living are significantly mediated by dissociative processes (van der Hart et al., 2004).

Please ensure that you read through all slides before proceeding by using the arrow keys on your keyboard or using the navigation buttons at the bottom of each slide.

The partial selves that hold traumatic experiences and awareness of various aspects of the trauma are generally preoccupied with maintaining safety through close attachment or defense. These partial selves may alternately spend significant periods of time presenting as a client’s working persona in the world.

Note

Psychedelic-assisted therapy with significantly dissociative clients is not advisable without a substantial foundation of structural integration work in advance.

Client Awareness

Especially key is client awareness of such dissociation and at least the beginnings of the ability to identify, name, observe, and consciously interact with dissociative phenomena within themselves. Health professionals should assume that whatever clients are aware of is the tip of the iceberg and proceed accordingly based on their observations in terms of the pacing of treatment.

With significant structural dissociation, parts of self of varying developmental ages and worldviews co-exist with minimal to no awareness of one another. These parts are highly avoidant—even phobic—of one another, and any co-consciousness between them (as often explored in internal family systems) is experienced as significant internal conflict, distress, and behaviour that is not aligned with the client’s best interests and stated values. The Self-system is incoherent, and thus significant impairments in relational capacity—particularly in intimate relationships—are present.

References

Fisher, J. (2017). Healing the Fragmented Selves of Trauma Survivors: Overcoming Internal Self-Alienation. Routeledge.

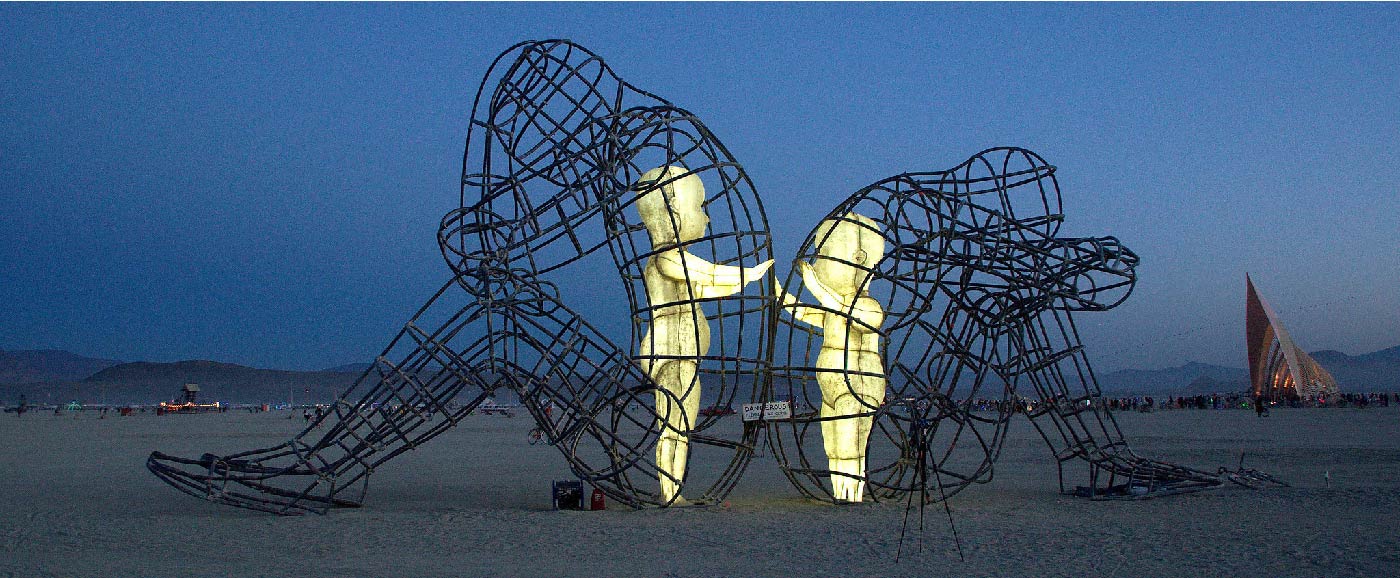

Kowshik, G. (2015). Love [Photograph]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/prodeezy/21210390060 Licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Nijenhuis, E. R. S., van der Hart, O., Steele, K. (2010). Trauma-related Structural Dissociation of the Personality. Activitas Nervosa Superior, 52, 1-23.

Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective neuroscience: The foundations of human and animal emotions. Oxford University Press.

van der Hart, O., Nijenhuis, E. R. S., Steele, K., and Brown, D. (2004). Trauma-related dissociation: Conceptual clarity lost and found. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 38(11-12), 906-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1614.2004.01480.x

Van der Hart, O., Nijenhuis, E.R.S., and Steele, K. (2006). The haunted self: structural dissociation and the treatment of chronic traumatization. WW. Norton.