Therapeutic Supportive Touch

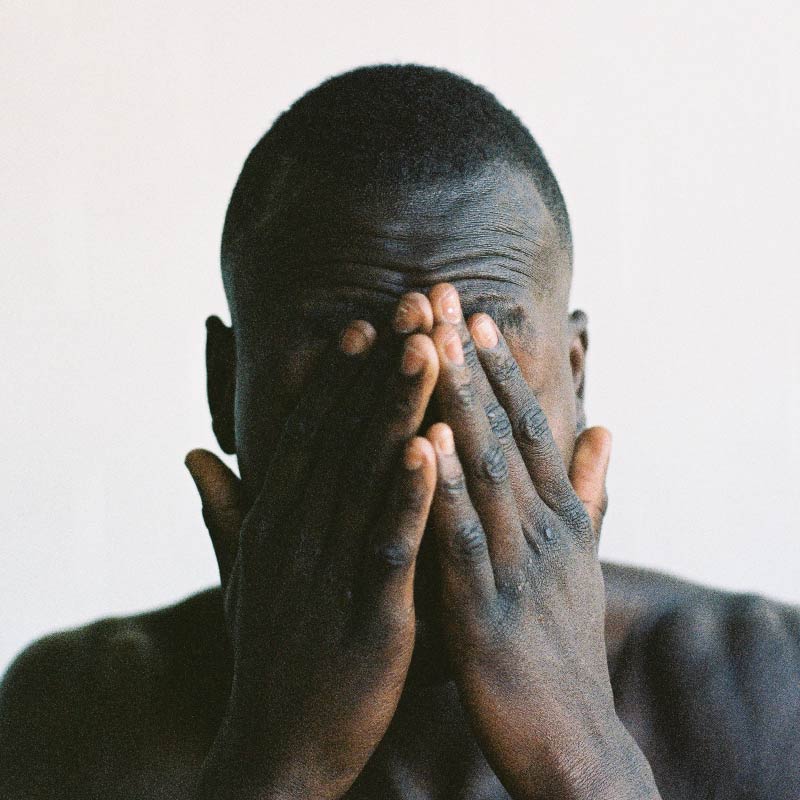

Touch is the first sense to develop in humans, while still in utero, and touch in early years is critically important for developing healthy attachment, interoceptive awareness, the capacity for emotional awareness, empathy, and self-regulation.

From a psychobiologically-informed somatic perspective, when used appropriately and with consent in therapy, touch can:

-

Help restore resilience and regulation

-

Be useful to repair attachment ruptures

-

Promote healthier and more accurate interoception

-

Create an embodied sense of safety and connectedness

-

Support better access to co-regulation and self-regulation

-

Help repair chronic somatic shame

-

Help with boundary development and agency

-

Provide powerful ‘corrective experience’ providing what was missing

According to Kathy Kain (2018) a senior faculty trainer with the Somatic Experiencing Training Institute, touch is particularly useful when:

-

It is helpful for the client to learn to differentiate between appropriate, caring touch and inappropriate, harmful touch

-

The touch helps the client integrate their change process more fully through of all the layers of the self

-

The touch helps the client remain resourced while managing their activation levels

-

The use of verbal language is limited, due to disability, language barriers (consent clearly navigated ahead of time, non-verbal responses to touch clearly monitored throughout process), or the effects of the psychedelic medicine

-

Working with early shock trauma that has a primarily physical origin (particularly when this occurs in the child/infant’s pre-verbal development phase)

-

Working with developmental disturbances that have a primarily physical origin, such as extended hospitalizations, particularly if the client’s symptoms are manifesting somatically

Note

However, touch may be counterproductive or even harmful, if not used ethically and appropriately. A health professional offering touch must have a nuanced understanding of their own personal history of touch, and how this might show up as countertransference. Health professional should familiarize themselves with the expectations of their regional regulatory bodies and workplaces when considering if and how to incorporate touch into their psychotherapeutic work.

In psychedelic-assisted therapy, withholding nurturing touch may be counter-therapeutic, and may even be perceived by the client (consciously or unconsciously) as retraumatization from the abuse of neglect.

Discussing Touch in Preparation Sessions

The use of touch is an expected area of discussion with the client in the psychoeducation and preparation stage of treatment and should be presented in written informed consent documents.

Please ensure that you read through all slides before proceeding by using the arrow keys on your keyboard or using the navigation buttons at the bottom of each slide.

Note

Consent for touch should be reviewed prior to ingesting a psychedelic medicine, and again in the therapeutic moment even if they fully consented in advance.

It is important that the pre-determined boundaries around touch defined by the client in advance of their psychedelic session be maintained throughout the session, even if the client later states a change of preference when in an altered state of consciousness. This is especially important when working with trauma, in keeping with the dictate that therapy progress only at the pace of the “slowest” or most “resistant” part of the client’s self.

Health Professional Tip

What are some alternate forms of touch in situations where physical touch has been declined?

In situations in which physical touch has been declined by the client or the health professional feels uncertain about offering it, the health professional may also offer presence by closing proximity, coming physically closer to but not touching the client. Other substitutes for the health professional’s touch may include having the client place their own hands on their body, touching and holding a soft object such as a stuffed animal, or using a fixed hard surface for resistance or pressure. A pillow can be placed between the health professional’s hand and the client’s body, so that contact can be communicated through tactile stimulus without direct touch. Lastly, the health professional may work in the imaginal realm with the client, guiding them through vividly imagining a given type of touch being offered and received and by whom, and then exploring that imagination through the core organizers of experience (Ogden & Fisher, 2015) and studying it with the client.

Video: Therapeutic Supportive Touch

On the next page, Dr. Devon Christie demonstrates how therapeutic supportive touch can be used during Medicine Sessions.

References

Kain, K. L., & Terrell, S. J. (2018). Nurturing resilience: Helping clients move forward from developmental trauma: An integrative somatic approach. North Atlantic Books.

Ogden, P. & Fisher, J. (2015). Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: Interventions For Trauma And Attachment. W. W. Norton.