Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy for Post-Traumatic Stress

As with acceptance and commitment therapy, psychedelic medicines also increase psychological flexibility as we have learned.

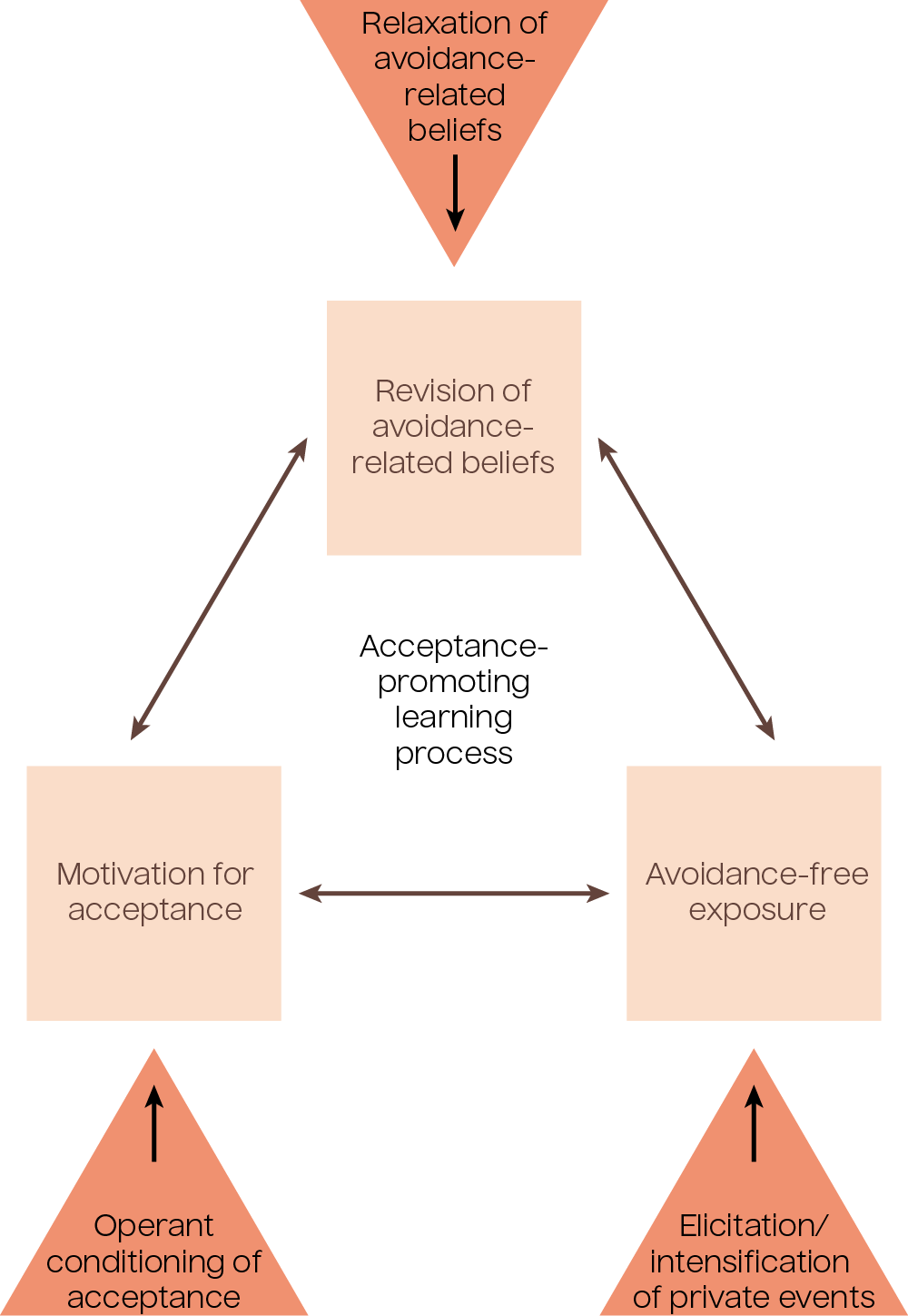

Psychedelic medicines also decrease avoidance and, through acceptance, promote learning processes. Below is a proposed model of acceptance-promoting learning processes in the context of psychedelic-assisted therapy for treating PTSD.

Figure 3.1: Psychedelic-therapy-specific factors facilitating the learning process. Adapted from Wolff et al., 2020.

A Spectrum of Self-Perspectives

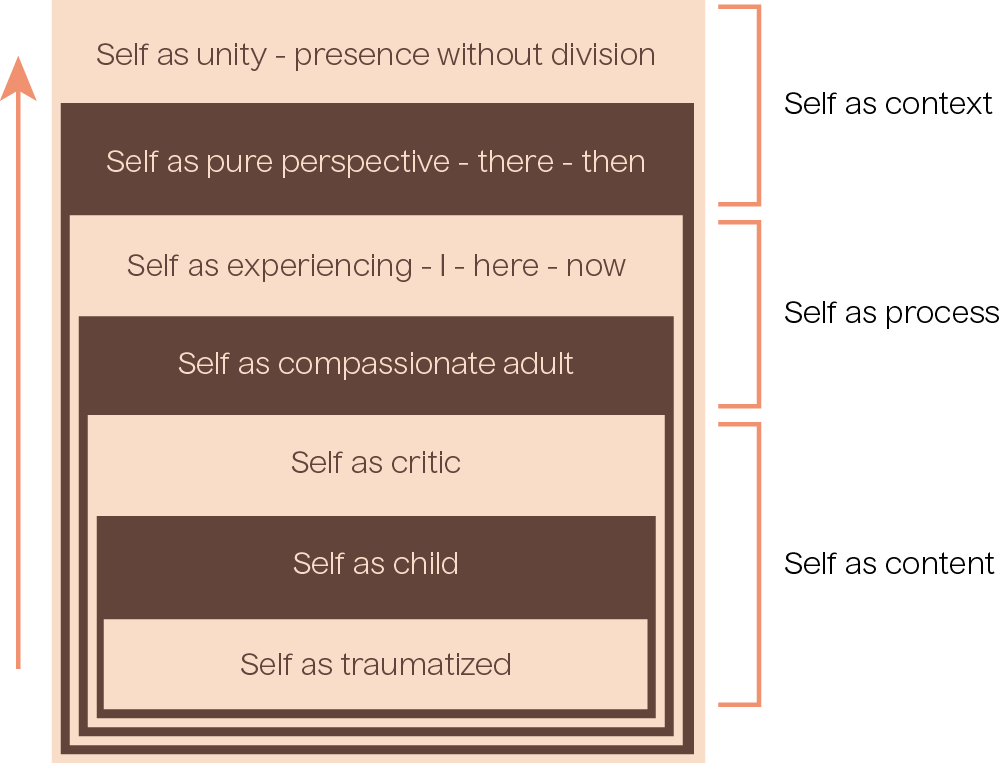

Psychedelic-assisted therapy supports a spectrum of self-perspectives, as we learned about in the Fundamentals of Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy course when we discussed internal family systems and parts work. The following diagram illustrates, moving from bottom to top, a journey toward the self-as-context in psychedelic-assisted therapy.

When people are fused in self-as-content perspectives (e.g. self-as-trauma, self-as-child, self-as-critic) there is less psychological flexibility and perspective taking and greater risk for psychopathology. Psychedelic-assisted therapy may powerfully promote alternative process and context-based perspective-taking, which may result in more compassionate self-perspectives or self-narratives, direct experience-based perspectives of self (distinct from any narratives), and ultimately unitive perspectives as described in mystical-type experiences.

Figure 3.2: Adapted from Whitfield, 2021.

Justice, Equity, Dignity, and Inclusion

Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities have not been well-represented in psychedelic research to date (Michaels et al., 2018). However, new research is showing that psychedelics may decrease the negative impact of racial trauma (M. T. Williams, A. K. Davis, et al., 2021). Recent research also suggests that these improvements in mental health may be mediated by increases in psychological flexibility (previously established with white research subjects) (M. T. Williams, A. K. Davis, et al., 2021), congruent with the Numinus approach to psychedelic-assisted therapy for PTSD.

MDMA-Assisted Therapy for Post-Traumatic Stress

As we learned in Molecular Foundations, MDMA-assisted therapy has been shown to be safe for those with chronic PTSD who have not had success with previous treatments (Bouso et al., 2008; Mithoefer et al., 2013). Additionally, MDMA-assisted therapy has been repeatedly shown to provide significant improvement in persons with PTSD, especially when it is moderate to severe (Jerome et al., 2020; Mithoefer et al., 2019; Mithoefer et al., 2011; Oehen et al., 2013).

A Phase 3 randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial of MDMA-assisted therapy with 90 participants suffering from severe PTSD and a range of common comorbidities displayed great efficacy from the treatment (Mitchell et al., 2021).

Long-term follow-up has displayed that benefits from the therapy are enduring, for example, lasting an average of 41 months in one study.

Relapse rate has also been shown to be low, for example, being 12.1% a year after treatment in one study

It was also reported that 67% of participants no longer met diagnostic criteria for PTSD (Jerome et al., 2020; Mithoefer et al., 2013).

A longitudinal pooled analysis of six Phase 2 trials displayed that PTSD symptoms were reduced 1-2 months after MDMA-assisted therapy, with symptoms continuing to improve at least 12 months after the treatment, which supported the expansion into Phase 3 trials and led to the FDA granting Breakthrough Therapy designation to this treatment method (Jerome et al., 2020; Mithoefer et al., 2019). Some research has been conducted specifically examining certain populations, such as service-related PTSD in first responders and veterans, where similar positive outcomes have been observed (Mithoefer et al., 2018).

Question

Why is MDMA so effective for treating PTSD?

MDMA's prosocial or "empathogenic" effects have largely been responsible for its use in psychedelic-assisted therapy (Bershad et al., 2016). This medicine can also serve to reduce negative distortion of self-relevant facts, a commonly seen aspect of depressive symptomology (Bershad et al., 2016). Likewise, it is believed that MDMA allows those taking it to speak more freely as a result of the dampening of their fears of social rejection, while attenuating responses to negative social experiences and emotional stimuli. This, of course, has direct implications in a therapeutic setting (Bershad et al., 2016).

MDMA is also thought to have the potential to make a client feel safer and more accepted during therapy, while also fostering greater empathic rapport with the therapist by altering recognition of and response to facial expressions (Bedi et al., 2009; Bershad et al., 2016; Grob & Poland, 2005; Hysek et al., 2012). Some of these effects may be linked to MDMA's capacity to reduce amygdala activity, as amygdala stimulation in animal models has previously been shown to be associated with states of conditioned fear, which resemble PTSD in humans. Reducing activation of the amygdala may serve to enhance interaction with the therapist during MDMA-assisted therapy (Davis & Shi, 1999; Rasmusson & Charney, 1997).

Ketamine-Assisted Therapy for Post-Traumatic Stress

While less robust than the research literature on depression, there is now a growing body of evidence supporting the efficacy of ketamine for PTSD (Feder et al., 2021; Feder et al., 2014). This has led to a general recognition among clinicians that ketamine is a valid treatment choice for PTSD, particularly treatment-refractory PTSD (Cigognini, 2017; Dougherty et al., 2018; Slomski, 2014). Even more so than with depression, effective pharmacological treatments for PTSD are limited, which makes ketamine an increasingly attractive pharmacological option. This is particularly true given the rapid onset of PTSD symptom reduction with single-session ketamine administration (Dougherty et al., 2018).

References

Bedi, G., Phan, K. L., Angstadt, M., & de Wit, H. (2009). Effects of MDMA on sociability and neural response to social threat and social reward. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 207(1), 73-83.

Bershad, A. K., Miller, M. A., Baggott, M. J., & de Wit, H. (2016). The effects of MDMA on socioemotional processing: Does MDMA differ from other stimulants? J Psychopharmacol, 30(12), 1248-1258.

Bouso, J. C., Doblin, R., Farré, M., Alcázar, M. A., & Gómez-Jarabo, G. (2008). MDMA-assisted psychotherapy using low doses in a small sample of women with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychoactive Drugs, 40(3), 225-236.

Dames, S., Kryskow, P., & Watler, C. (2022). A Cohort-Based Case Report: The Impact of Ketamine-Assisted Therapy Embedded in a Community of Practice Framework for Healthcare Providers With PTSD and Depression. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12(803279).

Davis, M., & Shi, C. (1999). The extended amygdala: are the central nucleus of the amygdala and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis differentially involved in fear versus anxiety? Ann N Y Acad Sci, 877, 281-291.

Feder, A., Costi, S., Rutter, S. B., . . . Charney, D. S. (2021). A Randomized Controlled Trial of Repeated Ketamine Administration for Chronic Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(2), 193-202.

Grob, C. S., & Poland, R. E. (2005). MDMA. In J. H. Lowinson, P. Ruiz, R. B. Millman, & J. G. Langrod (Eds.), Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Textbook (4 ed., pp. 274-286). Williams and Wilkins.

Hysek, C. M., Domes, G., & Liechti, M. E. (2012). MDMA enhances "mind reading" of positive emotions and impairs "mind reading" of negative emotions. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 222(2), 293-302.

Jerome, L., Feduccia, A. A., Wang, J. B., Hamilton, S., Yazar-Klosinski, B., Emerson, A., . . . Doblin, R. (2020). Long-term follow-up outcomes of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for treatment of PTSD: a longitudinal pooled analysis of six phase 2 trials. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 237(8), 2485- 2497.

Mitchell, J. M., Bogenschutz, M., Lilienstein, A., Harrison, C., Kleiman, S., Parker-Guilbert, K., . . . Doblin, R. (2021). MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD: a randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled phase 3 study. Nat Med, 27(6), 1025-1033.

Mithoefer, M. C., Feduccia, A. A., Jerome, L., Mithoefer, A., Wagner, M., Walsh, Z., . . . Doblin, R. (2019). MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for treatment of PTSD: study design and rationale for phase 3 trials based on pooled analysis of six phase 2 randomized controlled trials. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 236(9), 2735-2745.

Mithoefer, M. C., Mithoefer, A. T., Feduccia, A. A., Jerome, L., Wagner, M., Wymer, J., . . . Doblin, R. (2018). 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in military veterans, firefighters, and police officers: a randomised, double-blind, dose-response, phase 2 clinical trial. Lancet Psychiatry, 5(6), 486-497.

Mithoefer, M. C., Wagner, M. T., Mithoefer, A. T., Jerome, L., & Doblin, R. (2011). The safety and efficacy of {+/-}3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy in subjects with chronic, treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder: the first randomized controlled pilot study. J Psychopharmacol, 25(4), 439-452.

Mithoefer, M. C., Wagner, M. T., Mithoefer, A. T., Jerome, L., Martin, S. F., Yazar-Klosinski, B., . . . Doblin, R. (2013). Durability of improvement in post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and absence of harmful effects or drug dependency after 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamineassisted psychotherapy: a prospective long-term follow-up study. J Psychopharmacol, 27(1), 28- 39.

Oehen, P., Traber, R., Widmer, V., & Schnyder, U. (2013). A randomized, controlled pilot study of MDMA (± 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine)-assisted psychotherapy for treatment of resistant, chronic Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). J Psychopharmacol, 27(1), 40-52.

Rasmusson, A. M., & Charney, D. S. (1997). Animal models of relevance to PTSD. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 821, 332-351.

Whitfield H. J. (2021). A Spectrum of Selves Reinforced in Multilevel Coherence: A Contextual Behavioural Response to the Challenges of Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy Development. Frontiers in psychiatry, 12, 727572.

Wolff, M., Evens, R., Mertens, L. J., Koslowski, M., Betzler, F., Gründer, G., & Jungaberle, H. (2020). Learning to Let Go: A Cognitive-Behavioral Model of How Psychedelic Therapy Promotes Acceptance. Frontiers in psychiatry, 11, 5.